How the Plant-Based Diet Made Me an Overeater {REVISITED with more honesty}

(This post is also a podcast episode! Listen here.)

One year ago I blogged about how the plant-based diet made me an overeater.

A lot has happened since.

After the post, hundreds (I’m not exaggerating for impact) of people sent me an email saying that my experience was THEIR experience.

“I feel like I am so similar” was a common phrase.

Here’s one of those emails:

“When I first went plant-based, my weight dropped beautifully for the first 40 pounds. Then the weight-loss stopped, so I cut back a little more and I lost another 10 pounds, but then it just stayed there. No matter what I did it just stayed there.”

We all hit a weight we couldn’t move past.

No matter how plant perfect we were eating, or how much exercise we incorporated, the scale would not budge.

For a lot of the people I talked to, (and I’m included in this group) this barrier happened at a lower weight.

Meaning, our weight was in the “normal” or “healthy” range for our height but we still had visible body fat. And I’m not talking about vanity fat “a little here or there.”

In my case, my stomach was still hanging over my pants and I had chronic, painful chafing along my armpits and thighs from constant rubbing.

I wasn’t comfortable physically and I didn’t like how I looked.

Then I had my body fat measured.

I was at the tippy top end of what was considered “healthy” even though I was at a “healthy” weight.

“You have a really high percentage of body fat for your weight,” the technician told me.

Before I can continue this story, I need to first explain how the plant-based diet made me an overeater. (Don’t worry I’m not blaming kale.)

The plant-based community puts a lot of pressure on being perfect.

I saw this in the vegan movement too, though in a different way. With vegans, your membership card was revoked if you ate a hot dog, or in my case, used the wrong hand soap.

In the plant-based movement, there became this attitude that anything that was wrong with you was your fault for not being perfect.

If you weren’t losing weight, for example, it’s because you weren’t being perfect. You were eating oil, or sugar, or too many nuts, or not enough greens, or cheese.

And that’s not entirely untrue.

You can do any diet or lifestyle wrong, and it DOES come down to what you put in your mouth with weight-loss (more on that soon), but it’s also not as simple as “eat this, but not that” to lose weight.

Plants do not have magical calories that don’t count.

So, how did I become an overeater?

If you read any of the plant-based diet books, attend a conference, or watch one of the films, you get the impression that:

You can eat as much as you want. As long as it’s plant foods, especially whole foods close to nature. Don’t count calories or pay attention to portions.

Some of the experts say EXACTLY that outright.

Others send it more subliminally.

For example, they would share a recipe on their blog or Facebook. Someone would inevitably comment asking for calories or nutritional information, and they would get a response that you don’t need to focus on calories or portions when you eat this way (or something like that).

Monkey see. Monkey do, too.

Rip Esselstyn once bragged to me that he ate 22 (22!) of his burgers in one sitting. Another time I had lunch at FOK’s office and they fed me, I’m really not joking here, over 40 oranges and at least 100 strawberries for lunch. They kept piling more on my plate, rattling off something about how it’s mostly water and I needed to eat more because “it’s only fruit.”

I stuffed myself.

Another time I told Jeff Novick I ate a whole bag of frozen cherries for a snack – was that too much? And he replied, “only 1?”

(I have dozens of stories like this.)

Then there were the conferences where I watched these experts getting plate after plate of food. HUGE plates of food.

The one time when I stressed concern that I had overeaten (three plates of food) I was told not to worry about it. “You can’t gain weight on this food.”

But I did?

Point is, I was under the impression (and based on the responses, it appears many of you were too) that you can eat a lot. And that you SHOULD eat a lot. Eat as much as you wanted. Eat until you feel “full.”

So I did.

I ate and ate.

I quickly developed a habit of having 4 plates of food at a meal, all the while patting myself on the back for being so healthy.

For example, I would eat 4-6 bunless bean burgers, plus a huge "gorilla" salad, and 2-3 potatoes cut into fries for dinner. And I would still have room for 3-4 bananas blended as ice cream for dessert (and a snack later on).

After my original blog post, I got this email from FOK:

“For the record, it is not FOK's position that anyone can eat all they want on a whole-food, plant-based diet and maintain an optimal bodyweight. Our position is that one should eat until comfortably satiated.” (The email also said if I ate lower calorie foods I didn’t need to control my portions.)

WHAT IS COMFORTABLY SATIATED??!?!?!!

I have never found this “comfortable satiation” EVER.

My stomach has exactly three settings:

- I’m HUNGRY

- I’ve eaten but I could still eat more

- OMG I ate way too much I can’t move

If this sounds familiar, you’re not alone. It’s normal.

In fact, “comfortably satiated” doesn’t exist for most people.

Scientists still have not figured out what makes us “feel full.” It seems to be a combination of environmental clues, thoughts we had before eating, how much we smell and taste our food, how long we’ve been eating, how much we ate yesterday, and a myriad of other factors.

We don’t stop eating because our stomach is full, except in very extreme cases like Thanksgiving dinner.

Brian Wansink Ph.d (out of Cornell, like Dr. Campbell) has spent his career studying this very topic: Why do we overeat. What makes us feel full. and so forth.

Of all the important, life-changing lessons Wansink has taught me, nothing has been so impactful as this:

“Short of eating until it hurts, most of us seem to rely on size – the volume – of food to tell us when we’re full. We usually try to eat the same visible amount we’re used to eating. That is, we want to eat the same size lunch we did yesterday, the same size dinner, the same size of popcorn… We don’t stop eating because our stomach is full except in very extreme cases…”

(Wansink talked about how even when we think we can’t possibly eat any more, when the dessert comes out, we magically have more room.)

This is where I admit I became an overeater.

Mostly because I got used to eating a lot of volume.

Some of that came from those “eat all you want” messages, some from chasing the “comfortably full” illusion, and some because I just didn’t know how to structure my meals or build a meal that was satisfying, satiating, AND calorically correct for my biological needs.

This part you all know:

When I started using my meal plans consistently, I finally broke my weight barrier.

I lost an additional 13 pounds. (I’m lower than my high school weight!)

AND I have maintained that weight for THREE YEARS.

(I’m still amazed because I was a chronic yo-yo-er before.)

Before strict compliance with the meal plans (but plant-perfect) vs. me last week.

Now I get why body builders do that weird pose. There's no other way to really capture a photo of your abs!

In the past when I gained weight, or I couldn’t lose, I blamed my lack of perfection.

I blamed the occasional oil or vegan junk foods, and sure, those foods were doing me no favors, but that wasn’t the sole culprit.

Because even when my diet was beyond “perfect” (there was a point where I’d eliminated ALL sugar, salt, oil, alcohol, and even pureed foods foods like hummus or applesauce. I basically was only eating whole fruits and vegetables) I STILL didn’t lose weight.

I still didn’t break my barrier and then I started to GAIN WEIGHT.

I GAINED 7-8 pounds in three weeks eating vegetables!

That’s when I had my “coming to Jesus” moment.

To lose weight (again) and keep it off, I had to come to terms with how much I need in a day, and that it can’t be a free-for-all.

At least not for me.

I HAVE to pay attention to total calories and portion sizes too.

The meal plans make it really easy on me since it’s already planned out.

You could do it yourself, or you can do it with me.

Here’s the beautifully simple part: weight-loss is physics, the law of thermodynamics. You have to consume less energy than you burn (create a deficit) to lose weight, which can be accomplished in one two ways: from input or output.

(Side note: In helping dozens of Meal Mentor clients lose weight, I find the input side is the easier strategy for most folks. You have total control over what goes in your mouth AND it tends to be easier to, say, stop drinking wine than to start a 5x a week 5am gym regimen, for example.)

But here’s the not-so-simple part: a calorie is not always ‘a calorie’.

For starters, not every calorie is nutritionally equivalent.

Intuitively you know that 100 calories of carrot cake isn’t the same as 100 calories of carrots.

Not every calorie is absorbed the same way, either.

For example, calories from predigested foods (like smoothies) or highly processed foods (like Oreos) are absorbed much more easily than whole foods. Meaning, you might not even absorb the full bioavailability of the calories in an orange, but you’re probably going to absorb every last calorie in a Dorito.

(This echoes what Dr. McDougall says about oil being easily converted to fat on the body, “That the fat you eat is the fat you wear.” He’s not wrong. “From your lips to your hips” is very real, except that it doesn’t apply ONLY to fats, according to new research.)

And don’t forget: Not every calorie satiates in the same way.

You’ve experienced this before when you ate a doughnut and were starving an hour later.

But even whole plant foods vary greatly in satiety.

That was one of my biggest problems.

I was eating healthy, “perfect” foods, but they weren’t satiating me so I would eat more looking for that elusive “comfortably satiated” dragon, all the while resetting my volume expectations (or “appestat” as I like to call it, short for appetite thermometer) to HUNGRY HUNGRY HIPPO.

And this is another reason why I finally lost weight with the meal plans: They didn’t just teach me calories and portions, they taught what a meal needs to look like to actually satisfy me.

How to combine nutritious foods to feel satisfied so I DON’T overeat or feel deprived.

There’s also new research that cooking methods, gut bacteria, the composition of the food, and our genetics determines how many calories we actually absorb when we eat. (FYI some people absorb calories more easily than others. It’s not purely about differing metabolism as we once thought.)

I follow all this research obsessively.

After my blog post last year, and hearing from so many other people who were struggling, I decided to get down to the bottom of it. Figure out WTF was going on.

I’ve read an insane amount of books and studies. I’ve talked with and listened to dozens of experts in a variety of field from Wansink (above) whose focus is on how our environment makes us overeat, to people who study feces and gut bugs.

I’ve uncovered a lot and that’s what I’ll be talking about in upcoming episodes of my new podcast, Shortcut to Slim (a research podcast on diet and nutrition) – This blog post has been recorded as episode 1!

But briefly…

What I’ve come to understand is that any diet works for weight-loss (provided that diet creates a calorie deficit).

It doesn’t matter if you’re low carb, low fat, paleo, vegan, or eating only tacos.

Now, you might feel like garbage on an all cupcake and tequila diet, and that diet might put you at risk for other health issues (like hypertension and cirrhosis), which is why I still advocate a whole foods, plant-based diet all around.

Might as well do yourself a favor.

(Plus, not all calories are the same, remember? So it’s not a straight math formula anyway.)

But the reason why I lost weight beautifully in the beginning was because although I was overeating, there was still a deficit compared to my prior diet. (Even though I was also physically eating more VOLUME than before, the total calories were still less because bean burgers have less calories than cheese pizzas.)

HOWEVER, as you lose weight, that deficit window gets much, much smaller.

There’s little margin for error (which I learned the hard way).

When you shrink, how much you eat has to shrink too.

Many of the people who reached out to me after my blog post joined Meal Mentor and broke their barriers as well. My story continued to echo theirs.

Even those that didn’t join, but started practicing some form of input control, also had success.

Bottom line: It’s not about being “perfect”, though making good choices certainly makes it easier, just like it’s a lot easier to run a marathon if you quit smoking first.

The plant-based diet works. And it works for a lot of people. Part of why it works is because the foods can be low calorie (creating a deficit without volume deprivation) but there’s no such thing as calories that don’t count either.

If you want to start using the meal plans that changed my life and broke my weight barrier go here.

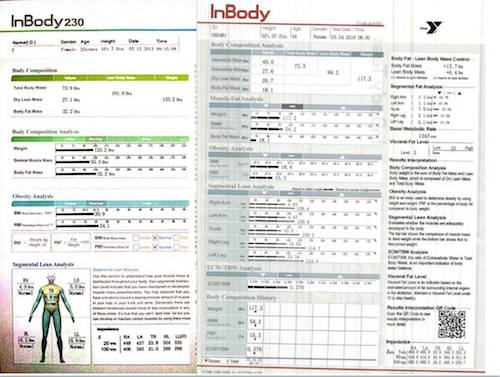

Here’s an image of my recent body scan:

What's amazing to me (other than being 15% body fat, self high-five) is that compared to my last scan in 2013, I ONLY LOST BODY FAT. Muscle mass, water, bone density, etc. is identical.

I LOOK so much more muscular and lean now, but that physique was there all along, hidden under fat.

In 2013 I was shelling out THOUSANDS on a personal trainer. Now I just do some yoga and follow the meal plans. If this is not a testament to the power of plants and that abs are made in the kitchen, I don't know what is.

Finally I must say one more thing:

I find with these kinds of posts and/or pictures like what I’ve shared here, people tend to use them attack me, saying I’m anorexic, and/or or I’m not sympathetic to people with eating disorders or food issues.

I’ve been very open (and very public) about my struggle with overeating (see above) and comments telling an overeater they are anorexic, or accusing them of not eating, or telling them to go eat, is about the most painful, unhelpful, and detrimental thing you can say to them.

Additionally, accusing someone – anyone – of having an eating disorder (or disordered eating) when they really don't, does a huge disservice to those who actually do.

It's important that we talk about our struggles with food, whatever they are... or our hurdles with weight-loss, and OUR SUCCESSES and that we can do it without being judged or attacked. (Plus if you really do care or have concern for someone, pull them aside. Saying it on social media is bullying. It's asking others to stand behind you and gang up on them. If they really ARE in a bad place, think about what that bullying might do.)

DON'T LET THE INTERNET HELP YOU FORGET THERE IS A REAL PERSON A LOT LIKE YOU BEHIND THE SCREEN.

I would rather keep my personal battles and triumphs to myself, but I share them publicly so that they can help others and tell anyone who has ever struggled YOU ARE NOT ALONE.

And you do not have to sit in the dark and feel like no one else understand.

Finally, to the people who accuse me of not being sympathetic to those who are in recovery, I can only say this: I have to live my life and I can't do that if I'm always worried what other people might think or how they might feel or react.

I don't expect everyone to toe the line on my behalf. Not my parents or siblings, friends, coworkers, or other people I follow on the internet.

My struggles are *my* struggles, my challenges are *my* challenges, and for the rest of my life I'm going to be around food, and people eating food, and food images, and supermodels in LA. I have to find a way to deal with that and the thoughts I have when I see it, hear it, and so on. I must work my program and my steps and build my own support system. I do supplement it with the support of many of you, who help me in my darkest hours. Just knowing you’re there can be a comfort, but I also can’t live in a bubble. I am sympathetic, but that sympathy doesn’t mean I will alter my absolute commitment to total transparency.

My therapist helped me see I can’t change every person or every situation, but I can change how I feel or act in it. How I talk to myself is decided only by me. How I interpret others’ actions or words is within my sole control. I have so many strategies for dealing with my demons, adding more each day. It’s the program, and you work it, but ultimately, it’s all about you and not the bubble.